“The value of antibiotics lies not in the volumes sold, but in the life-saving impact they deliver.”

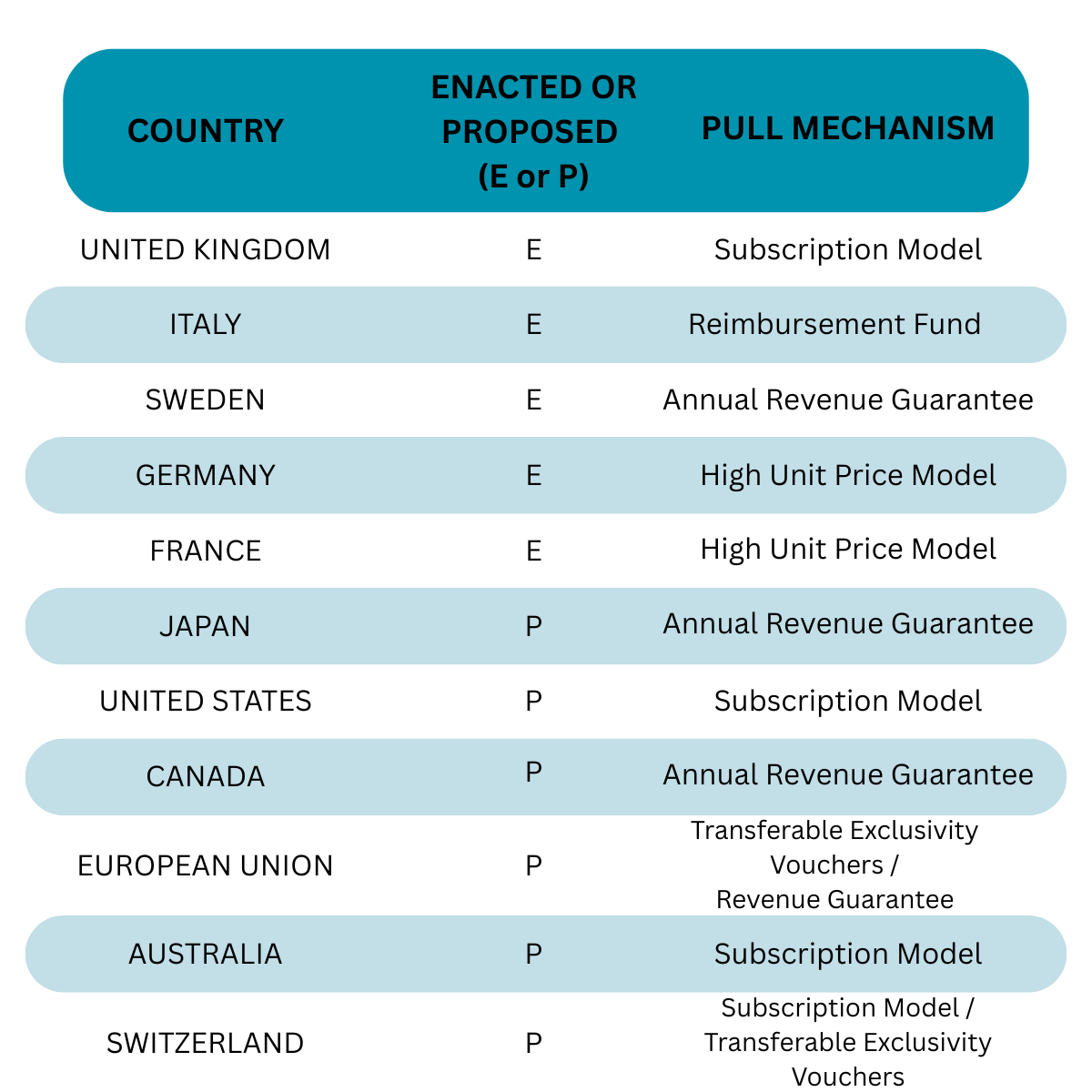

The way that efficacious antibiotics are paid for has already changed in the UK and Italy. Many other countries and regions are in the process of piloting or introducing their own new reimbursement schemes. The emerging remuneration models are forcing a total revision of the return on investment (ROI) perspective. This has dogged drug development in this area for decades: expectations of poor financial returns stymied antibiotic innovation as investors and major pharma companies directed funds elsewhere. But since the early 2020s radical moves to change how life-saving antibiotics are paid for are paving the way to a situation in which it is plausible to foresee current developmental stage antibiotics generating $350 million to $500 million once they launch in the 2030s.

The world has entered a startling new era in medicine. In fact, it started a few decades ago. It seems to have crept up on us; but in truth, it was always predictable.

The Golden Era of antibiotic drug discovery came to an abrupt end in the 1960s as the rate of discovery of new antibiotics slowed dramatically. It soon dawned on medicinal chemists just how difficult it was to develop from scratch drug compounds that can kill bacteria. All, or most, of the “easy” molecular designs based on a handful of natural antibiotics, had been exploited. Twenty years later, in the 1980s, the latest novel broad-spectrum antibiotics were launched. No new broad-spectrum antibiotics have been launched since; and only a mere handful of derivative or narrow spectrum products have made it to the market in the last two decades.

Bacterial resistance to well-known and widely used antibiotics has continued to increase steadily against a background of no fundamentally new antimicrobial agents coming to the market. According to a recent WHO report it is anticipated that within the next 6 or 7 years levels of bacterial resistance to a host of critical antibiotics will exceed 40% in Europe. It is already at, or approaching, this level in some regions of the world.

Bacteria become resistant to antibiotics through a number of mechanisms but genetic mutation, conferring non-susceptibility to these drugs, is a major driver of this phenomenon. Mutations arise randomly during DNA synthesis which occurs each time a bacterium prepares for replication. At 20 to 30 minutes bacteria have generation times that are over 525,000 times faster than humans’ generation times (25 to 35 years). The opportunity for spontaneous, advantageous mutations to occur is immense. Vertical DNA transfer – that is, transmission of DNA from mother to daughter cell - is also accompanied in nature by horizontal gene transfer whereby bacteria pass DNA elements to neighbouring bacteria. This, quite literally, adds another dimension to the spread of antibiotic resistance. Consequently, there are now numerous multi- and pan-drug resistant pathogenic bacteria cohabiting with us.

Once a resistance mechanism has arisen to a given antibiotic it does not take long for a shift in that resistance to arise as a derivative new antibiotic is introduced. The time lag between first clinical use and onset of resistance in the world of antibiotics has been diminishing dramatically in recent years, from over 15-20 years (up till the 1980s), to less than a year (seen for many 21st Century antibiotics). Resistance to a fifth-generation cephalosporin antibiotic, cefiderocol, was actually recorded before it completed clinical trials.

In an effort to contain the levels of drug resistance there is a drive to use what few remaining effective antibiotics we have as sparingly as possible: there is a close correlation between intensity of usage and emergence of resistance. This makes clinical sense whilst we buy time to develop new antibiotics. But this has uncovered to an economic conundrum.

We want new life-saving antibiotic drugs. However, for many patients the duration of antibiotic treatment will be a matter of days, perhaps up to a couple of weeks. This amounts to fewer antibiotic drugs being sold per year than, say, the gargantuan volumes of drugs sold for the treatment of chronic conditions such as some cancers, auto-immune disease, and metabolic conditions such as osteoporosis. In the past this meant that antibiotics, as commercial products, just did not make economic sense. To a first approximation, it costs just as much to develop an antibiotic as it does a daily-used drug for a chronic disease. The difference in financial returns simply has not supported a commercial argument for the development of new antibiotics.Consequently, for most of the last 40 years many major pharmaceutical companies have shied away from this arena of drug development. In their place SMEs have emerged as the main source of innovation, accounting for more than 80% of all commercial R&D in antibiotic development. These SMEs typically have fewer than 10 employees and less than 12 months’ funding in the bank.

A GLIMMER IN THE GLOOMA seminal report published in the UK in 2016 highlighted the growing crisis. In 2022, the UK initiated a pilot study to test the notion that the value of antibiotics lay not in the volumes of drugs sold, but rather in the societal and clinical impact that their life-saving performance can bring. This shifted the mindset away from value being attached to volume of sales and towards value being attached to the access to, and availability of, effective new antibiotic products. Crucially, a core tenet of the new thinking is that antibiotic use is not abolished altogether and is designed to incentivise new antimicrobial drug development. Clinicians can focus on whether a given antibiotic is the appropriate treatment for their patient and if so, can prescribe sparingly.

This radical new thinking blossomed into what is now called the UK Subscription Model. It has been likened in one analogy to having a subscription for an entertainment streaming service (cf. NetFlix: you pay a fixed fee and have access to all the entertainment available, whether you use it or not). Another analogy likens the approach to having a well-inspected and reliable fire extinguisher in your home, available to be used, but something you dearly wish never to have to use.

In the UK Subscription Model the basis of revenue returns to the manufacturer is the pinned to the intrinsic life-saving value placed on the product, coupled with there being constant access to it, regardless of how many units of drug are actually used. It is intended to create a more compelling commercial proposition (guaranteed minimum annual revenue) whilst enabling an informed and considered reluctance to use the antibiotics unless they are absolutely necessary.

The UK system can now return just under £24 million per year per antibiotic drug. In 2024, following the UK pilot study, the first two drug products were adopted into the Subscription Model. Pfizer’s/AbbVie’s ceftazidime/avibactam combination product, Ceftaz®, and Shionogi’s cefiderocol are the trailblazers. Notably, neither is a particularly differentiated antibiotic. Avibactam in Ceftaz® rescues the original efficacy of ceftazidime (a third-generation cephalosporin) through its beta-lactamase inhibitory activity. Cefiderocol represents a fifth-generation cephalosporin cleverly designed to get through the two membranes that encase Gram-negative bacteria. The latter has evidently triggered bacterial resistance but is nonetheless a potent antibiotic in infections mediated by susceptible pathogens.

Outside of the UK there have been different approaches taken. The European Union (EU) has recently announced its plans to issue Transferable Exclusivity Extension Vouchers (TEEVs). The manufacturer, upon receiving regulatory approval for a new antibiotic would receive a TEEV which can be used to extend the patent life of any other marketed drug. Since most of the developers of new antibiotics are one-product companies, the value of the voucher will be realised by selling it to a major pharmaceutical company. With GLP-1 receptor agonist products (Wegovy®, Mounjaro®) delivering double-digit billions of USD in annual revenue, one can envisage a path being beaten to the doors of Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly in the future.

Whilst the UK system has captured some headlines, France, Germany, and Sweden have all had systems in place which aim to encourage the availability of antibiotics to their respective healthcare systems. They all follow one variation or another of higher-than-typical reimbursement for valued antibiotics. France and Germany target novelty as well as efficacy. Sweden favours access and efficacy: there is no special provision for novel drugs.

Nations such as Canada and Japan have made slow progress and in the case of Japan appear to be considering particularly low revenue guarantees to manufacturers.

However, it would appear that the UK’s approach has some global appeal. Italy launched their own PULL system in July 2025, budgeting €100 million per annum to support availability of novel and efficacious antibiotics. Against the qualifying criteria for reimbursement eligibility, 7 drug products are already listed, and 2 more are expected to become eligible by the end of 2027.

Australia has concluded that their soon-to-be launched pilot should be operated essentially along lines of the UK Subscription Model. Switzerland is likewise considering a similar scheme alongside two others; interestingly one of which is based on the EU’s preferred TEEV approach.

The as-yet unratified PASTEUR Act, recently reintroduced in the US Congress for a third time, moots the notion of rewarding manufacturers who bring a new antibiotic to the market through a subscription-style multi-year drug supply contract. Figures of between $75 million and $300 million in guaranteed revenue are being discussed.

So, will all this activity encourage innovators?

An observational treatise published by Goh et al. (2025) builds on the notion of a (proportionate) “fair share” principle under which nations would effectively calculate a range of fair share revenue guarantees to manufacturers delivering qualifying antibiotics. There is a range from $258 million (low-end) to $562 million (high-end) with a mid-range figure of $363 million. This same fair share principle features in several of the global programmes, active or in planning, for incentivising new antibiotic development.

Notably, a patented drug compound commanding revenues of $363 million would rank in the top 235 drug products by revenue in the world. There is no exact figure for the total number of different drugs being sold at present but estimates range from 10,000 to around 14,000. Thus, even at the lower estimate, a drug that can realise $363 million would lie within the top 2.5% of global drugs by sales.

The riposte to all that would be: but no one gets close to those figures; we all know that antibiotics just do not make those figures – or anything like it.

Tell that to Pfizer, AbbVie, and Shionogi.

Ceftaz®, the combination product launched in 2015 and sold within the US by Pfizer and outside of the US by AbbVie, posted global sales of $330 million in 2024. Shionogi’s cefiderocol, launched in 2020, reported global sales of $219 million in the same year. The trend in both sales trajectories is still rising. Notably, both products are the first beneficiaries of both the UK and Italian subscription models.

Ceftaz® and cefiderocol are considered to be high impact antibiotics despite being based on a third-generation and a fifth-generation cephalosporin, respectively. Which just goes to show what a truly novel antibiotic could be worth medically and commercially going into the 2030s, by which time we can expect a lot more enactment of PULL incentives all round the world. And a much-depleted antibiotic pharmacopeia in desperate need of these new medicines.